Changing the trajectory of euthanasia

Belated media attention can’t change legalisation, but it reminds us that we still have choices to make.

They say that late is better than never, but sometimes there’s not much difference between them. On that score, it’s hard not to be frustrated by the recent investigative series from RNZ asking how ready we are for the new regime for euthanasia and assisted suicide to commence later this year. The coverage comes too late to inform Parliament’s decision to establish the regime in 2019 or the public’s decision to enact it in last year’s referendum. But while nothing can turn the clock back on those decisions, perhaps the belated attention can still be turned to good.

To begin, let’s consider what RNZ has been revealing about the nation’s readiness, or lack thereof, for the practicalities of euthanasia and assisted suicide. First, there are concerns that training will be inadequate, perhaps no more than an online course, meaning patients may be treated by a doctor or nurse practitioner who’s inexpert in managing pain and end-of-life issues. Then there are fears that very few medical practitioners will be willing to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide—a Ministry of Health survey found that only 10% of them were “definitely willing” with a further 20% “possibly willing”—so that “a small band of itinerant doctors with no connection to their patients may do the bulk of the cases.”

There’s international data showing that the lethal medications used don’t always work neatly and it’s also possible that, at least initially, these medications will be “off-label” and unregulated. In fact, Ministry of Health research noted that, "With all these forms of assisted dying there appears to be a relatively high incidence of vomiting (up to 10 percent) prolongation of death (up to seven days) and re-awakening from coma (up to 4 percent)." Lastly, it’s predicted that around 1100 people will request euthanasia or assisted suicide in the first year, with around 350 following through, but that evidence from overseas suggests the numbers will rise over the years.

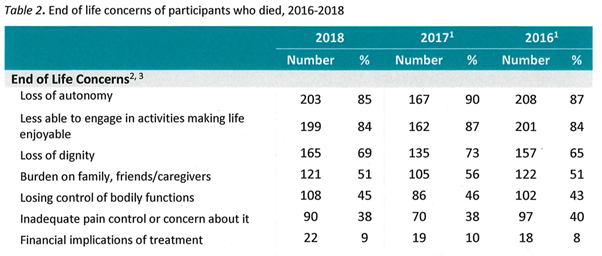

But these issues, troubling though they are, really only begin to scratch the surface. There’s another set of statistics that hint at what’s at stake, in the form of data from Oregon and Washington that show patients’ most frequent reasons from requesting assisted suicide are “loss of autonomy,” being “less able to engage in activities making life enjoyable,” and “loss of dignity”. This, I think, takes us to the heart of the matter, something that can’t be solved by mere practicalities like more efficiently lethal medication, or more time to implement the new regime.

When you really get down to it, the case for euthanasia and assisted suicide is mainly about personal autonomy, living with maximal freedom and dying that way too. Writing about the difference between those who tend to support euthanasia and those who tend to oppose it, legal academic Māmari Stephens has written: “We tend, I think, to divide into those two great camps: those for whom the idea of the autonomous individual is supreme, and those for whom human interconnectedness is the greater vision.” To many, autonomy is an appealing ideal. In fact, it seems to be the dominant ideal in our society, certainly on the evidence of the 65% majority that voted to bring euthanasia and assisted suicide into force in last year’s referendum. To my mind, autonomy has an important place, and human agency—the ability to make meaningful choices for yourself—is a part of a good and dignified life. But when autonomy is allowed to break free from the constellation of other values that should inform us, like solidarity, and become the guiding star we navigate by, its focus on individual choice inevitably produces a individualistic vision of life.

This self-centred vision will hollow out—is hollowing out—our society, and euthanasia and assisted suicide will only accelerate this trend. But here’s where all of us still have a chance to change this trajectory. While the kind of reporting we’re seeing from RNZ is too late to inform the crucial decisions about whether to implement euthanasia and assisted suicide, it reminds us of what’s at stake. And if you think, as I do, that the individualistic vision is not just bleak but dangerous, because it’s so frequently a reason for assisted suicide, then the hope is that we become a society where the choice to end your life exists but is not exercised.

That means providing and extending excellent palliative care, so that people have hope rather than fear for their final days. It means focusing on the wisdom and the contribution of the elderly among us, and learning from cultures that honour the aged and support them in intergenerational networks, rather than buying into the cult of youth and the inevitability of the retirement village. It means acknowledging the dignity of all people, regardless of ability or disability, not just when it’s time for a feel-good story but when issues of life and death are on the table. And, ultimately, it means accepting an interdependent vision of life in place of an independent one, recognising that we are connected to our neighbours by bonds of solidarity, that we have mutual obligations for the effect of our actions.

Perhaps this is a lot to ask. The experience of following, and participating in, the debate over euthanasia and assisted suicide certainly makes me think so. So does the inexorable rise in deaths from assisted suicide and euthanasia seen in other jurisdictions that have legalised them. But difficult is not impossible. We still have choices available, individually and collectively. It’s not too late to make them.