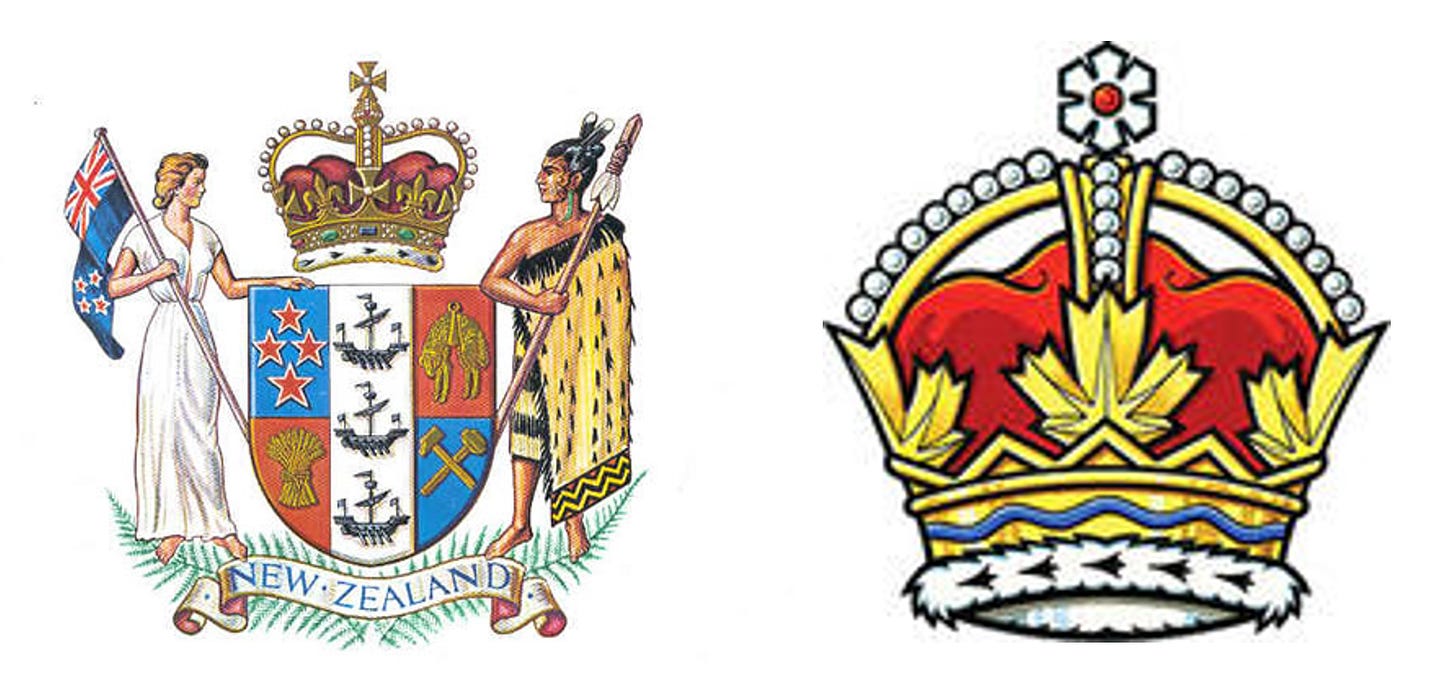

What is the modern monarchy? According to the Canadians, one thing it’s not is religious. They’ve recently changed their heraldic crown (the emblem representing the Canadian crown—there’s no physical version) by removing all the religious symbols. The cross at the top is gone, replaced by a snowflake. The fleur-de-lis, a symbol connected with the Virgin Mary, is replaced by maple leaves. To anyone who watched the intensely religious and specifically Christian event that was the recent coronation, this is all rather odd.

We humans are a mixed bag—sacrificial and selfish, noble and base, virtuous and vicious—and everything we create reflects this. Money facilitates commerce and stokes greed, the internet spreads love and hatred, and we make drugs that heal and addict. This is also true of the institutions we build and the people who fill them. Our parliamentary democracy is a great blessing, but it’s far from perfect. In the same week as the King’s coronation, Meka Whaitiri ditched Labour for te Pāti Māori because she missed out on promotion, and Elizabeth Kerekere resigned from the Greens amid a welter of allegations about who she called a “crybaby”. Contrast that rather self-centred politicking with the words of Jesus in the mouth of our new King: “I come not to be served, but to serve.”

The point isn’t that kings are necessarily better than politicians, but that they are explicitly accountable to something and Someone higher than themselves. Of course, this-worldly forms of accountability are also possible; MPs must face the voters, constitutional documents construct and limit power, social mores encourage some acts and stigmatise others. But all of these are as human, and as limited, as the people they hold to account. Only something other-worldly can call us to the higher standard that we can’t create ourselves.

There are many transcendent ideals and it matters which one we serve. If we believe life is a Darwinian exercise in the survival of the fittest then we’ll worship strength and vitality and expect our rulers to embody power and domination. Perhaps we’ll even dub them demi-gods or Ubermensch. But if instead we follow a faith that says the first shall be last, and that to rule is to serve, then perhaps we’ll crown a king in the way we saw at Westminster—with pomp and circumstance, but also with humility and reverence.

This is the meaning of the modern monarchy, as one of the few remaining institutions that points us to something bigger than us, something transcendent that calls us to higher and better things. Perhaps that occasion will inspire all of us to lift our gaze from the everyday symbols that characterise our ordinary existence—from snowflakes and maple leaves—to the eternal symbols that give our existence its deepest meaning—crosses and lilies that speak of sacrifice and redemption. If so, then perhaps we can say, like it really means something, God save our King.