Kintsugi, calling, and creativity

Calling is core to the Christian life and our role as co-creators, but we can’t hear it if we’re not paying attention

Kintsugi is the ancient Japanese art of restoring broken ceramics or pottery. A kintsugi artist joins these fragments with a golden lacquer—“kin” means gold and “tsugi” means to reconnect—and in the process creates something new, something transformed that is like but also different from what existed before. The artist Makoto Fujimura describes it as a “‘resurrection’ into use again of what is broken” and this, I think, is an incredible metaphor for what it means to be called as a Christian and to work out our calling, a task that’s getting harder in a distracted culture.

Calling is a concept with a rich Christian tradition. For centuries, people have spoken of a God-given “vocation”—derived from the Latin vocare, which means to call—as a way of understanding our purpose in the world. Paul expressed it like this in his letter to the Ephesians: “For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do.” The Westminster Shorter Catechism sums up the purpose of these good works as, “Man’s chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy Him forever.”

It’s a deeply counter-cultural message in this day and age, this idea that something or someone else—outside or above you—provides direction for your life. It’s the opposite of “you do you” individualism, which posits that everyone is entirely free to determine the meaning of their life. By contrast, Christians believe that we have agency and personal freedom, but that we are not the authors of meaning in the world, that the purpose of our freedom is to respond to this created order. It’s expressed in the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30); we receive our talents and abilities as gifts and we’re supposed to use them to be fruitful in the world. To a Christian, calling reflects the fact that He is the Creator, and we are His creatures—and yet, not only His creatures.

Astonishingly, God gives us a role as co-creators with Him, to help with the restoration of the world and the in-breaking of the new creation. This creativity is a core expression of Christian vocation, and one that I think is particularly relevant to our situation in a consumption-oriented, materialistic society. In such a society, we must ask ourselves how we can create, not just consume, and help arrest the slide into cultural, environmental, and spiritual exhaustion. This emphasis on creativity and restoration has parallels with kintsugi, as in the exhibition by kintsugi master Kunio Nakamura that featured the union of ceramics from conflicting nations—North Korea and South Korea, India and Pakistan, the UK and Ireland— to illustrate the possibility of reconciliation. In his book Art + Faith, Fujimura says:

“The Bible begins with Creation and ends with New Creation. Everywhere in between, Creator God (the grand Artist) beckons the broken, but creative, creatures (the little-‘a’ artists) to create shalom/peace in the face of our ‘Ground Zero’ reality all around us.”

But for a calling to be effective, it needs to be heard, and to be heard, we need to be listening. To be listening, we need to be paying attention, and in this day and age there’s no shortage of distractions. One example, a particularly pressing issue for Christians who are supposed to be “people of the Book,” is the rise of digital technology and the “attention economy”. In the attention economy, people make money (vast sums in some cases) by attracting our attention—which means distracting us from something else. Whether it’s a digital marketer’s click-through rate tracking our interaction with their carefully baited virtual hooks, or someone fishing for data, we are all immersed in this economy.

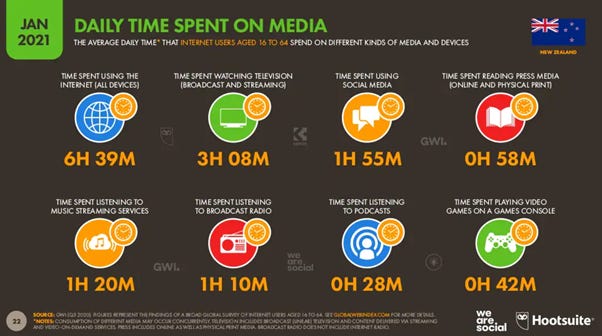

It turns out that New Zealanders spend over six and a half hours connected to the internet each day. Of that, some time is spent streaming TV, and nearly two hours is spent on social media. New Zealand teens are among the world’s most connected. These figures don’t tell us exactly what people are doing in all this connected time—they could be reading War and Peace on their tablet, or playing Grand Theft Auto—but it seems unlikely that all this online time is being invested in wholesome activities or thoughtful engagement with the world, as opposed to doom scrolling or curating a misleading social media presence.

In fact, I think there’s a reasonable chance that our state of constant connection is undermining reading, one of the main ways we listen and learn. In 2018, it was rather underwhelmingly reported that “86% of New Zealand adults had read or started to read at least one book in the past year.” In 2019, Read NZ noted that “in 2018 New Zealand came 30th out of 50 OECD countries in a study of childhood reading comprehension, a list that New Zealand topped in the 1970s.” Their research also found that, “New Zealanders believe they engage less deeply with online content than traditional reading material” and that “participants in this survey … are finding it hard to read longer content than in the past.”

In other words, the issue isn’t just what we’re reading or how much we’re reading, but how we’re reading. Read NZ’s research pointed to findings that digital reading does not typically equate to the kind of “deep reading” that engaging with printed material can foster:

“the move to engaging with material through ‘continuous partial attention’ means an increase in ‘cognitive impatience’. This leads to the loss of what Professor Maryanne Wolf has called ‘deep reading’ – the kind of reading that requires the reader’s complete attention to understand the thoughts on the page. This lack of engagement means opportunities to develop the brain circuitry needed for deep reading are absent, which may also affect the ability to engage in deep reflection and original thought.”

In the words of Professor Wolf herself:

“we may be spawning a culture so inured to sound bites and thought bits that it fosters neither critical analysis nor contemplative processes in its members.”

This brings us back to calling, and the risk that our hyperconnected culture and decaying reading habits are undermining our ability to pay attention. Professor Karen Swallow Prior says that, “Christianity is a religion of the Word. Christians are a “People of the Book.”” But if we’re losing the ability to read, or to make sense, let alone meaning, out of what we read, then how are we to engage with the Word? And if spending time in the Word is one of the main ways to listen and discern our calling, then how can we discover and engage with God’s call on our lives?

Renewing our capacity for reading and for listening is no easy task, but hard is not impossible. Although we’re expected to be connected, and there are legions of behavioural psychologists and engineers on the other side of our devices working on ways to get us to spend time on them, we have choices. Here are a few thoughts on practices that can help us.

First, we need accountability in community, to encourage and help each other to rethink our relationships with the things that distract us, whatever they are.

Second, we can look to resources like Digital Minimalism, which is all about using technology consistently with your values, and only when the benefits clearly outweigh the costs. And there’s The Tech-Wise Family, which describes steps we can take in our homes to maintain a healthy relationship with technology, including making sure we have plenty of good, engaging, non-tech activities in our homes, especially things that support our ability to create.

Third, we might review our personal practices. To give an example, my only social media account is LinkedIn, because I find it so cripplingly boring that it poses little danger of distraction. I deleted my Facebook and Twitter accounts when I realised that their costs outweighed any benefits I was receiving from them. And I now keep a book log to track my reading and, in a small way, to encourage myself to keep cultivating a reading habit.

Digital technology and the attention economy are pressing issues for our time, but if it wasn’t them it would be something else—being distracted from our calling is nothing new. In fact, part of the challenge in discerning our calling to co-labour with God and restore the world is that we are ourselves broken and in need of restoration. As the Bible puts it, we are “jars of clay” (2 Corinthians 4:7). We need kintsugi too. God’s calling isn’t just about how we engage with the world or about the tasks He gives us to do—it’s about our own redemption and sanctification.

So what does it mean to be both creatures and co-creators? “It means to be invited into a dance, invited by God’s grace to be on the stage, to step into a journey of New Creation that we do not yet fully understand,” says Fujimura. It means to serve as we are being served, to heal as we are being healed, and to respond to God, as the author and the originator of all that there is.

A great reminder and encouragement, thanks Alex.