Mar.23 | Technocracy, uniformity, and transcendence

It's time to return science to its rightful place | It is difficult for Te Pūkenga not to write satire | If we don't look to heaven for transcendence, we'll try to manufacture it on earth

What’s wrong with technocracy?

Technocracy is a popular dirty word. It’s become fashionable to complain about a “technocratic elite” re-shaping our society, but like many other words in political discourse it’s often used pretty loosely. When words are seen to have explanatory power, I think it’s important to ask what they mean and why people use them. Let’s start with the definition: technocracy means rule by experts, and its history can be traced to 1919 when one WH Smyth argued that a complex modern society needs “a supreme National Council of Scientists to advise us how best to live”. Since then, use of the term has waxed and waned but there’s been a sharp spike since 2008, proof that it’s a contemporary concern. I think there are good reasons for this concern because it’s an increasingly accurate description of our times and the growing supervision of science over society. Click here to keep reading

From uniform fonts to uniform thoughts

“It is difficult not to write satire,” said the Roman poet Juvenal nearly 2000 years ago. Te Pūkenga’s style guide is a good example of this. Like all good satire, it reveals what lies beneath the surface of public and political discourse and holds it up to ridicule. But, unlike Juvenal who wrote his satires intentionally, Te Pūkenga has accidentally satirised itself with its hand-wringingly earnest attempt to impose a set of written norms on its staff. Amusing and cringe-inducing though it is, there’s a serious issue at stake, for control of language equals control of thought. Te Pūkenga is the one organisation born to rule the vocational education sector, though according to its style guide we’re not allowed to use the VE words. Formed out of 16 polytechs and 9 industry training organisations, the fledgling behemoth is apparently in the early stages of creating a uniform identity across its disparate departments, including by the imposition of a uniform style. Fair enough. Organisations need clear guidelines for written content, particularly large ones with far-flung provinces to rule. It’s the content of this particular style guide that’s so amusing, and concerning. Click here to keep reading

Tom Holland and Paul Kingsnorth on the inescapable human desire for transcendence

Tom Holland and Paul Kingsnorth are two of the most interesting writers and public intellectuals around these days, so when I saw the two of them in conversation my ears pricked up. Holland is well-known as the author of Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, which explores the profoundly (and, he says, inescapably) Christian shaping of modern Western culture and civilisation. Kingsnorth was already a famous novelist and environmental activist when he wrote the mega-hit article, “The Cross and the Machine”, about his journey to becoming an Orthodox Christian. Their conversation is wide-ranging and fascinating—I can’t do it justice here (watch the whole thing below) but I want to pick out one exchange that I think is especially important because it reveals something fundamental about human nature that most of our public discourse simply doesn’t reckon with.

Kingsnorth:

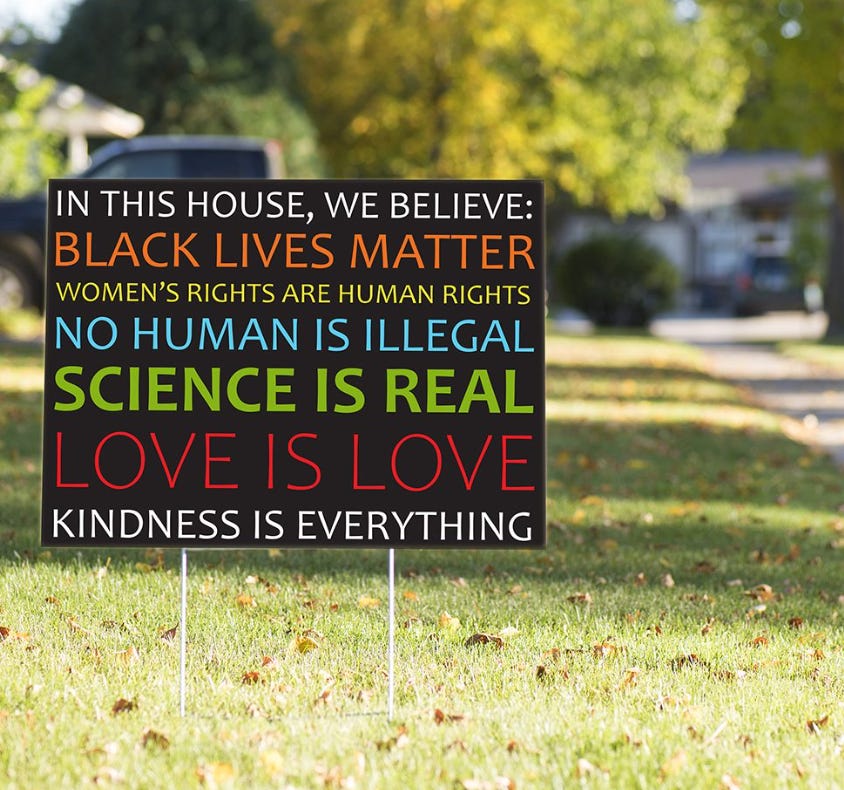

left progressive politics … it’s the Sermon on the Mount without God … without forgiveness…

Holland:

it’s a … form of Christianity that rejects the Augustinian idea of original sin and says that it is possible to become perfect, that by your good deeds you can attain heaven and the problem with that, although it sounds kind of wonderful and inspirational, is that if one can become perfect then it also entitles you to sit in judgment on those who have not made themselves perfect.

Kingsnorth:

once you take God out of the picture you only have the material realm and then you start to deal with the desire for heaven in the material realm which becomes Utopia which becomes a political aim and it’s to be achieved on Earth through either politics or technology. That takes us into the age of everything that happened in the twentieth century with the desire for utopian ideologies to create a Heaven on earth but then it takes us also into what’s happening in the twenty-first which is where we try to achieve the same thing with technology … its as if Western humanity has severed itself from the source of its values and denies them but can’t stop behaving as if they were still there but now they’re centred in us so we become the gods, we become the creators, and that’s the thing that really disturbs me, what we think we can create with that power.

Humans desire transcendence and if we don’t find it in heaven, we’ll seek it on earth—and if our society and our politics doesn’t take account of this, we’re condemned to the doom loop of utopian ideals, winner-take-all politics, soul-destroying materialism and ever more aggressive virtue-signalling. There is an alternative, but I suggest you listen to the conversation to hear more about that.