May.23 | Fascism, monarchy, anxiety, and Red Peak

Who's a fascist? | The meaning of the modern monarchy | Rethinking children's use of social media | Don't believe everything that you breathe

Who’s a fascist?

The next time you hear someone use a term like “fascist” ask them to justify it—and if they can’t, they might just be the problem.

Imagine an axe with a handle made of wooden rods bound together with a red strap. This is the Roman fasces, a symbol of power and authority. A hundred years ago this symbol was claimed by a new political movement in Italy, headed by Benito Mussolini, who named themselves after the axe because it represented “the power of unity around one leader”. From these Fascists we get “fascism,” used first to describe an ugly political ideology and misused now to conceal an ugly political prejudice. There are plenty of political swear words in our lexicon, from the relatively benign (“ideologue”) to the toxic (“Nazi”). “Fascism” belongs at the top end of this spectrum, a brutal reality which doesn’t stop people who should know better wielding it against those who disagree with them. Here’s a recent example—former minister and current Green MP Julie Anne Genter lashing out at a supposed “radical right wing Christian fascist movement.” (Click to keep reading)

God save our King

What is the meaning of the modern monarchy?

What is the modern monarchy? According to the Canadians, one thing it’s not is religious. They’ve recently changed their heraldic crown (the emblem representing the Canadian crown—there’s no physical version) by removing all the religious symbols. The cross at the top is gone, replaced by a snowflake. The fleur-de-lis, a symbol connected with the Virgin Mary, is replaced by maple leaves. To anyone who watched the intensely religious and specifically Christian event that was the recent coronation, this is all rather odd. We humans are a mixed bag—sacrificial and selfish, noble and base, virtuous and vicious—and everything we create reflects this. (Click to keep reading)

Social media and poor mental health

Time to rethink how we let children use smartphones and social media.

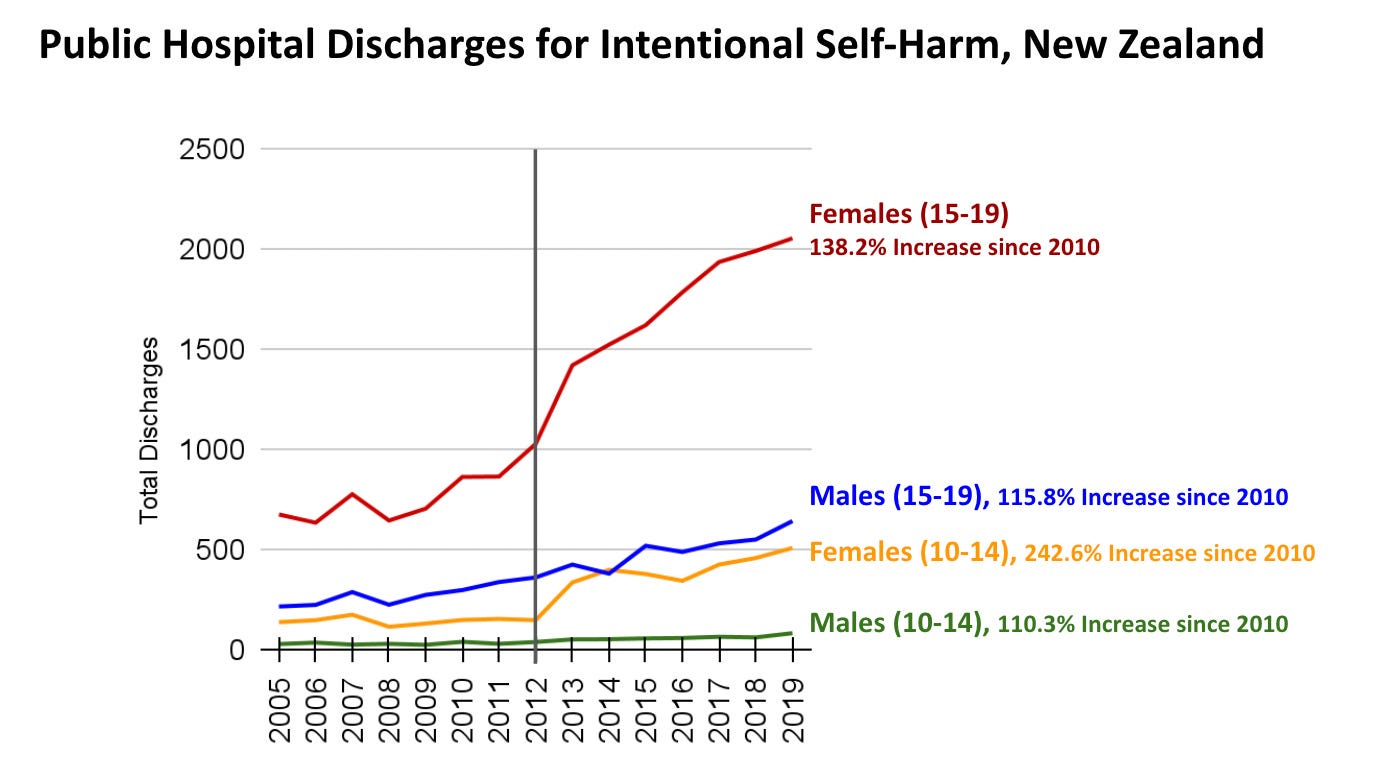

Between 2012 and 2019, the number of New Zealand teens hospitalised for self-harm doubled. In 2020, a quarter of all 15-24 year old females said they had been diagnosed with anxiety, a steep increase from five percent in 2010. Note this is all prior to the pandemic-inspired lockdowns which are often said to have cratered teen mental health, so what’s going on? According to Professor Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues, it’s due to fundamental changes in childhood:

“it’s the transition from a play-based childhood involving a lot of risky unsupervised play, which is essential for overcoming fear and fragility, to a phone-based childhood which blocks normal human development by taking time away from sleep, play, and in-person socializing, as well as causing addiction and drowning kids in social comparisons they can’t win.”

The most important of those changes, they believe, is the rise of social media. (Click to keep reading)

Don’t believe everything that you breathe

From the archives (February 2021): In which I attempt a not-entirely ironic mash-up of Beck’s “Loser” and the Red Peak flag debacle to consider whose voices dominate social media

In the halcyon days of 2015, we apparently had so few real problems that we could afford to hold a pointless referendum on the New Zealand flag. The referendum was established carefully: an expert panel was commissioned to engage with the people, flag designs were sought and earnestly considered, and in accordance with the law passed by Parliament four flags were chosen by the panel to be voted on by the public. Then social media got involved. The resulting shambles isn’t just an embarrassing historical footnote. It’s also a good example of something illustrated by recent British research: social media might be like the air that we breathe, but it’s dominated by a small subset of influential voices.

Back in 2015, social media unrest had started to build when the panel’s four chosen designs were released, perhaps because they all looked more like designs for a beach towel than a flag. The Twitterati sprang into action, an online petition was launched, and in response to this public pressure a fifth design, known as Red Peak, was added to the panel’s shortlist via emergency legislation. Speaking in Parliament, Green MP Gareth Hughes said the change was “about this House listening to the public and listening to the groundswell of support.” But despite this digital groundswell and the significant advantage of being the only option that looked like an actual flag, Red Peak crashed and burned in the eventual referendum. How could such an apparently popular choice fail so badly? Recent British research sheds some light on this apparent conundrum. (Click to keep reading)