Social media and poor mental health

Time to rethink how we let children use smartphones and social media

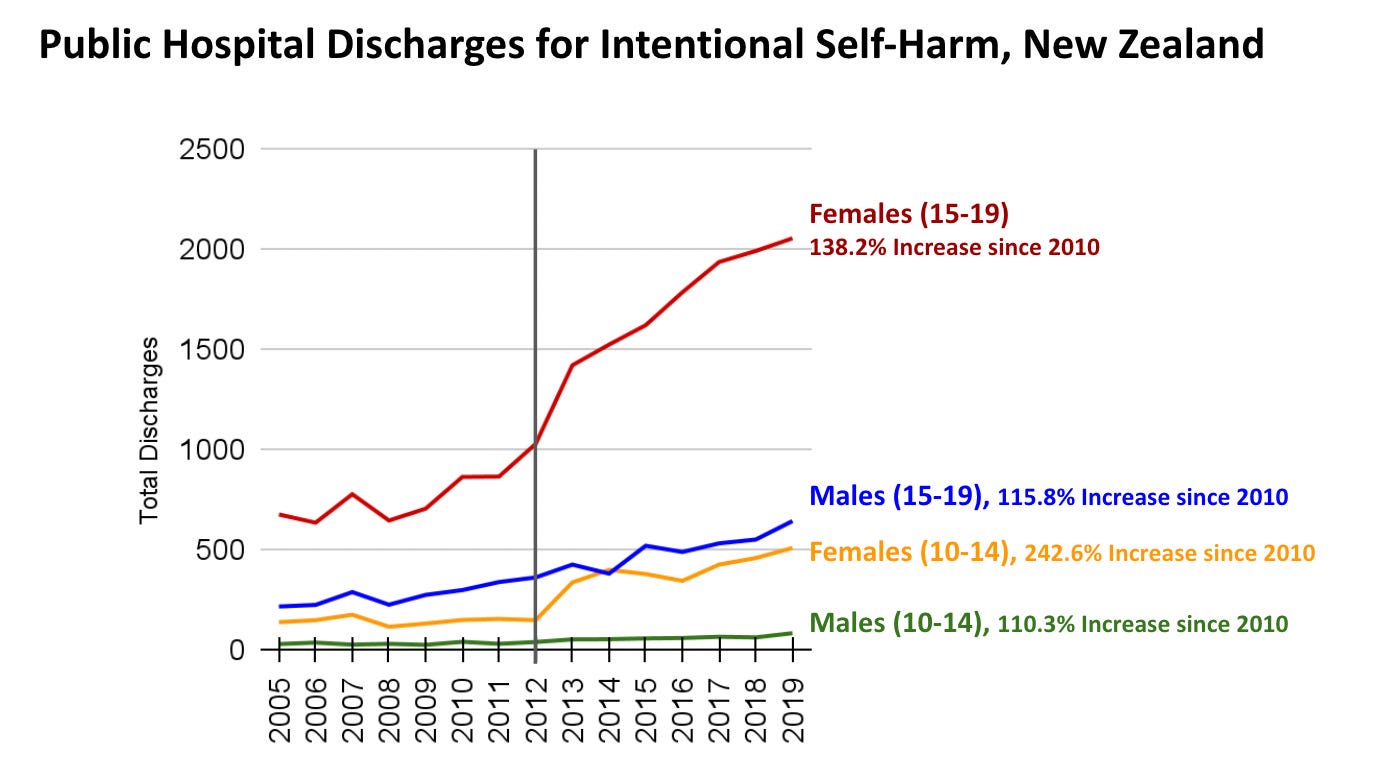

Between 2012 and 2019, the number of New Zealand teens hospitalised for self-harm doubled. In 2020, a quarter of all 15-24 year old females said they had been diagnosed with anxiety, a steep increase from five percent in 2010. Note this is all prior to the pandemic-inspired lockdowns which are often said to have cratered teen mental health, so what’s going on? According to Professor Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues, it’s due to fundamental changes in childhood:

“it’s the transition from a play-based childhood involving a lot of risky unsupervised play, which is essential for overcoming fear and fragility, to a phone-based childhood which blocks normal human development by taking time away from sleep, play, and in-person socializing, as well as causing addiction and drowning kids in social comparisons they can’t win.”

The most important of those changes, they believe, is the rise of social media. Teens started having widespread access to iPhones around 2011-12, and not long after Instagram use took off. Suddenly, teens were spending long periods on highly visual media, sharing images of themselves with others who would judge them, on platforms that provided addictive feedback loops. Not only did this fuel anxiety-inducing comparisons, it also drove teens apart as online interaction replaced real-life relationships. As Haidt and his colleagues put it, “teens were already socially distanced by 2019” and the results are grim: “Teen mental health plummeted across the Western world in the early 2010s, particularly for girls and particularly in the most individualistic nations.”

So far, so moral panic-y, you might be thinking, perhaps even recalling media reports of studies that apparently showed social media has the same impact on wellbeing as eating potatoes. Haidt and his colleagues drill down into studies like this in great detail and chart their research journey publicly and transparently, through open access Google docs and their After Babel substack. They take the critiques and counter-arguments seriously, obviously mindful that their work could have a significant impact on real lives. For example, one recent post is titled, “Why Some Researchers Think I’m Wrong about Social Media and Mental Illness,” and the title is followed by 6,000 words responding to leading critics. There’s a lot of detail in there, most of it accessible to a non-academic audience (they take great pains to explain technical and statistical methods) and the end result is a high degree of confidence in their conclusions. For example, they point out that the “potatoes” research looked at the effects of digital media, not social media, on teen mental health. They didn’t stop at making that point either, but went further and tested the “potatoes” dataset themselves focusing on social media—and found the negative effects on mental health they had predicted.

In an age when science is both revered and highly contested, this kind of open hypothesising and transparent research journey is an immense public service. Anyone can follow along as the researchers marshal their evidence, admit their doubts, engage their critics, and draw their conclusions. And what are those conclusions? Ultimately they’ll be presented in a book, but in a recent post Haidt offers three recommendations that he’s considering for parents, schools, and lawmakers:

A) Encourage a norm that parents should not give their children smartphones until high school. …

B) Encourage all K-12 schools to be phone-free during the school day. …

C) Congress should raise the age of “internet adulthood” from the current 13 (which was set in 1998 before we knew what the internet would become) to 16 …

Haidt’s careful to point out that smartphones and social media aren’t the only cause of the issues he’s identified—he’s also deeply concerned about the rise of “safetyism” and the decline of children’s unsupervised free play. But smartphones and social media are clearly significant and based on the evidence presented it’s pretty hard to disagree with the three recommendations above. As the evidence continues to mount, perhaps we’ll finally have a genuine debate about the costs and benefits of social media in our teens’ lives—and our own.